Information

Here is a takeaway and checklist to help you plan and implement task analysis and chaining.

Task analysis and chaining are two evidence-based interventions that can be used to break down a complex task into small steps that are easier to manage for the learner. Task analysis is used to describe each of the steps, and chaining is the suggested strategy for teaching those steps. The most appropriate skills for task analysis are those that can be divided into small steps, including daily living, communication, social, and academic skills.

Learning Objectives

After working through this section, you will be able to:

Developing a Task Analysis

The task analysis process consists of defining each of the steps or behaviours that occur as part of a larger sequence, or chain, to accomplish a task. Following are the steps for developing a task analysis:

1. Identify the steps in the chain.

There are three methods that can be used to identify the steps in the chain. Click each method to learn more.

Observe a skilled person going through the desired behaviour sequence.

Observe a skilled person going through the desired behaviour sequence.

For example, you could watch another child tie their shoes and write down the steps you observe.

Consult specialists or people skilled in performing the task.

Consult specialists or people skilled in performing the task.

A person who has taught a child to tie their shoes can help produce an effective task analysis.

Practice the behaviour; do the steps yourself.

Practice the behaviour; do the steps yourself.

2. Describe the steps in an observable, measurable, and accurate manner.

The more complete and accurate the task analysis is, the more successfully the learner will be able to acquire the skill.

It is more effective to describe the steps using action verbs and to include only one action per step. The steps must be adapted to the learner’s level (e.g., the steps will be more detailed for a younger learner than for an older learner).

3. Validate the steps.

Regardless of the method chosen, it is important to validate the steps and ensure that the material chosen corresponds well to the context and to the needs of learners and their families. All that is required is for another person (i.e., a colleague, another learner) to carry out the steps exactly as written in the list, using the materials indicated.

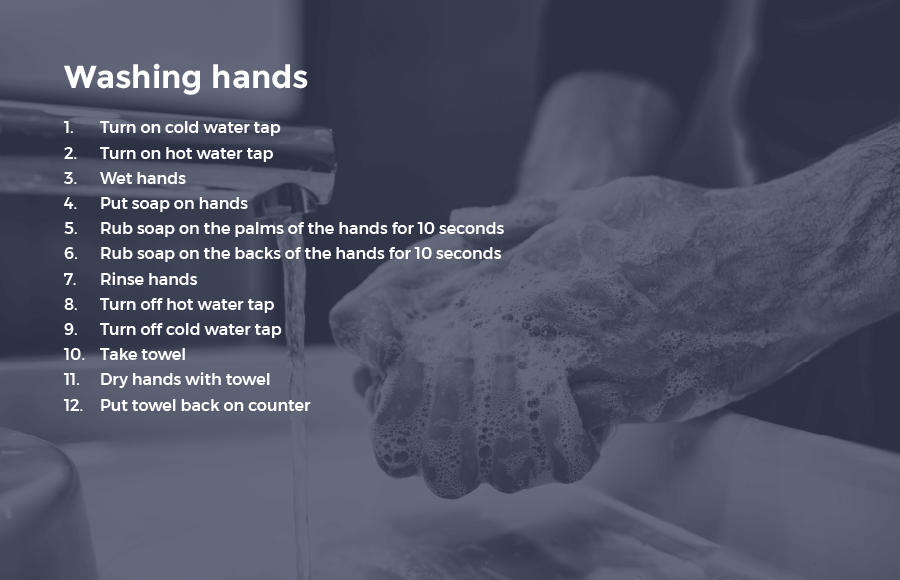

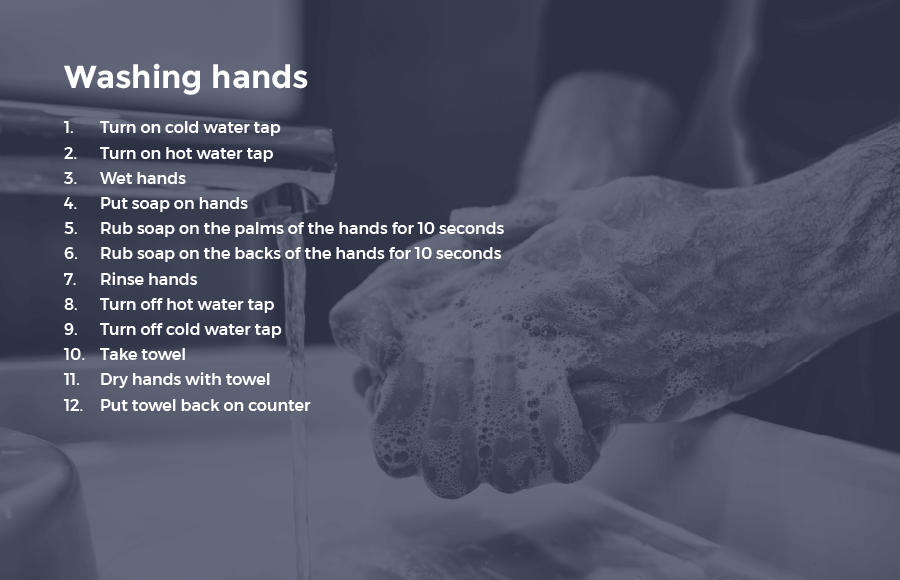

Click on the image to display a sample task analysis for the skill Washing hands.

This skill may be described differently depending on the context (e.g., washing hands at home or washing hands in a public washroom). That is why it is important to individualize the task analysis according to the learner’s needs and check with the learner or the learner’s parents that the list of steps is appropriate.

Chaining

Chaining is a method of teaching skills in several steps. This teaching approach is often used in combination with task analysis. It is based on the reinforcement of a specific sequence of behaviours leading to the acquisition of a targeted skill.

Chaining is a method of teaching skills in several steps. This teaching approach is often used in combination with task analysis. It is based on the reinforcement of a specific sequence of behaviours leading to the acquisition of a targeted skill.

To use chaining, a step in the sequence is chosen as the teaching target. Two evidence-based approaches, prompting and reinforcement, are used to teach the targeted step. Thus, the learner is first prompted to perform the step, and the behaviour is encouraged by a reinforcer.

Since a task analysis comprises several steps, you need to decide which step will be taught first. There are two strategies, forward chaining and backward chaining, which determine which step in the sequence will be targeted for teaching.

Forward Chaining

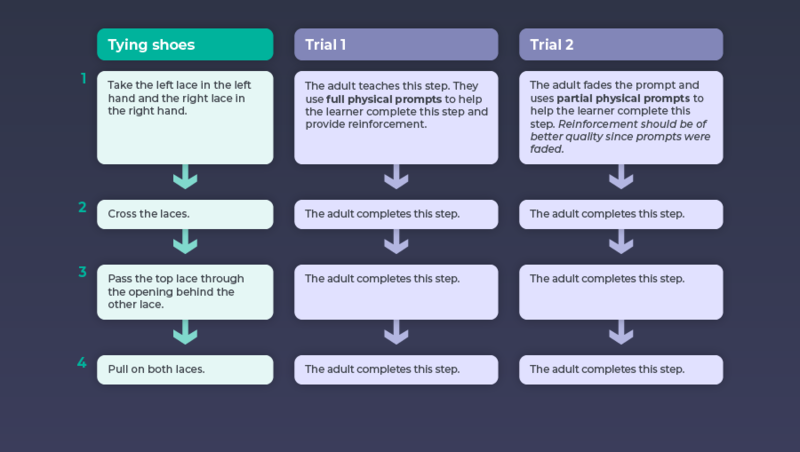

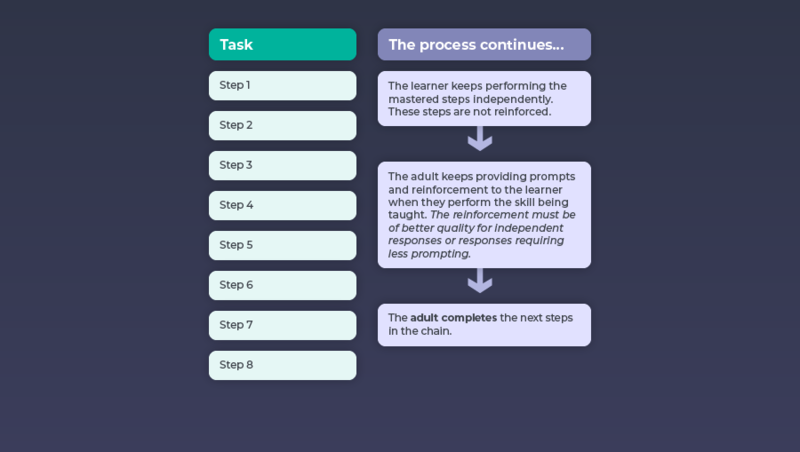

Forward chaining teaches the steps of the chain in the order that they would normally occur (i.e., from the first to the last step) and offers reinforcement to the learner for each step taught. Then, the adult goes through the next steps or helps the learner to do them. This is a trial. During subsequent trials, the adult continues to teach the first step using the prompt and reinforcement until it is mastered, and completes the rest of the sequence themselves. The adult gradually fades the prompt from one trial to another as the learner progresses, providing higher-quality reinforcement for independent responses.

Once the learner masters the step independently, the adult repeats the same teaching process for the next step. At this point, the adult stops reinforcing the earlier steps that the learner can perform independently.

The individual thus learns to perform one step at a time, but this step is never separated from the chain. The person understands that one step leads to the next, which facilitates the transfer of learning.

For certain skills, such as tying shoelaces, pulling a zipper up or following a recipe, learners can simply observe the adult performing the steps they have not yet mastered. However, for certain skills such as washing hands, the adult will have to guide the learner physically.

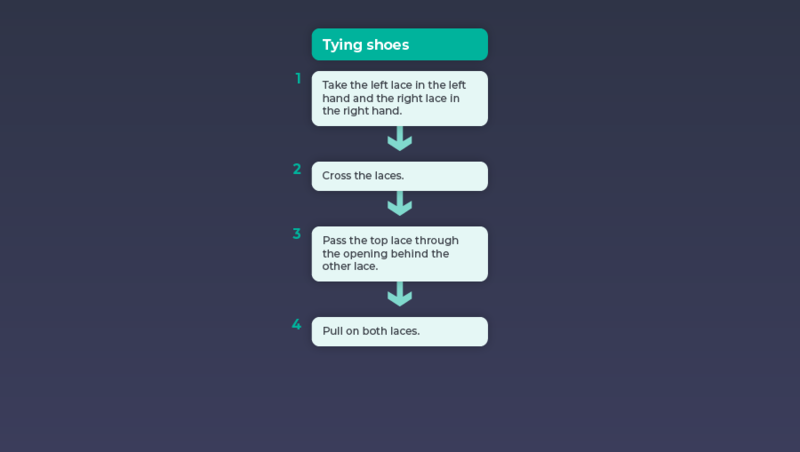

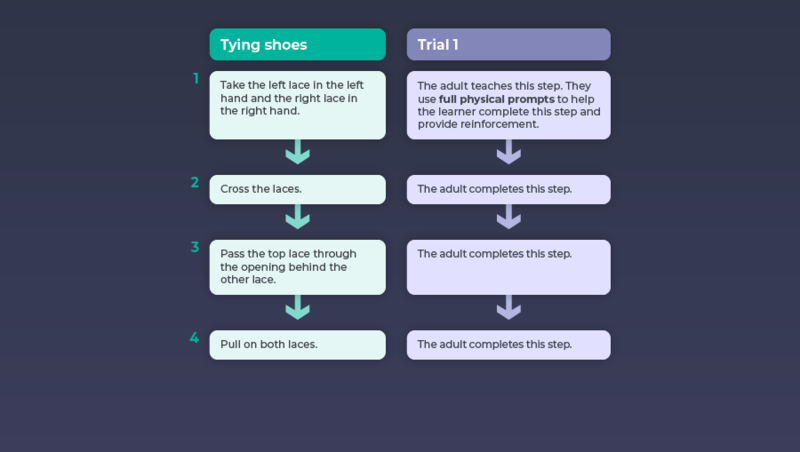

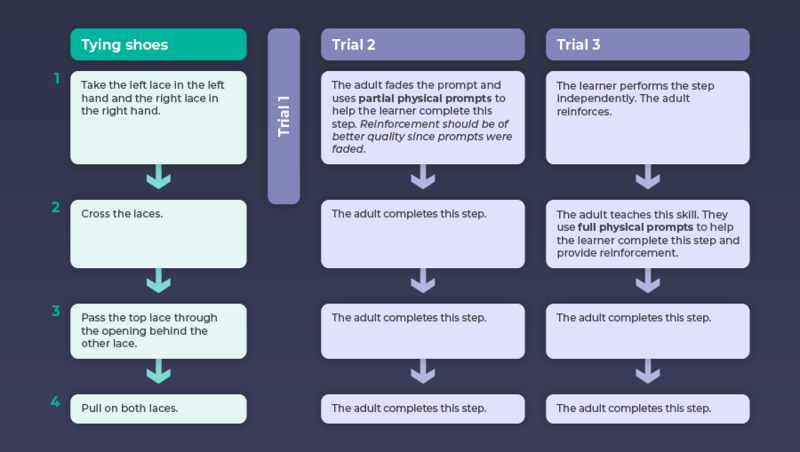

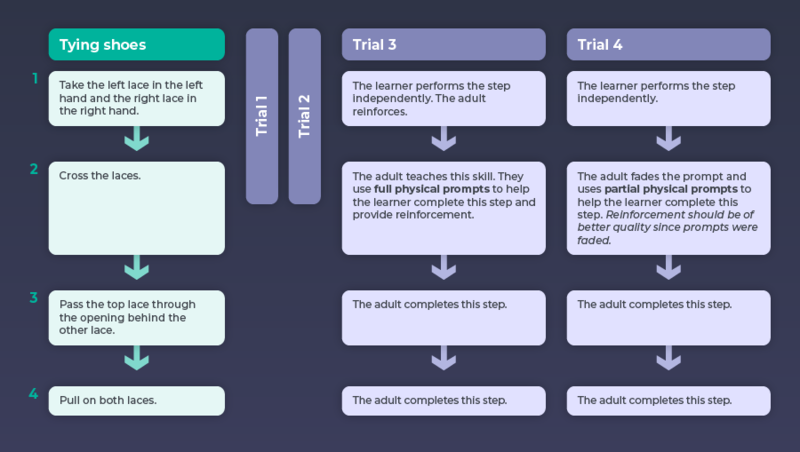

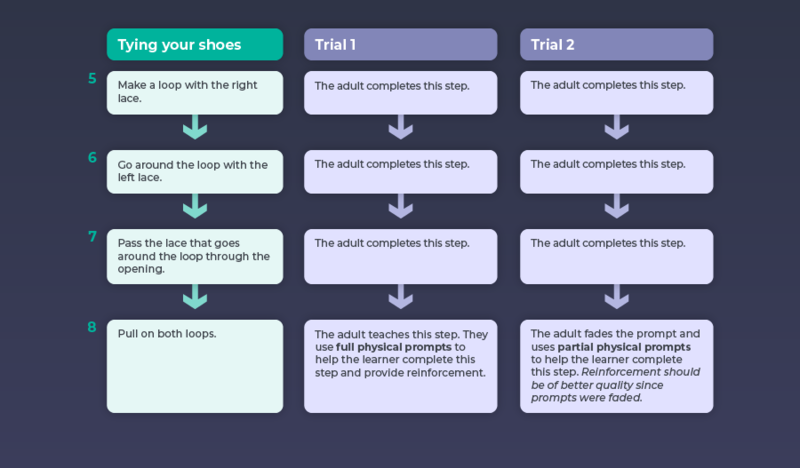

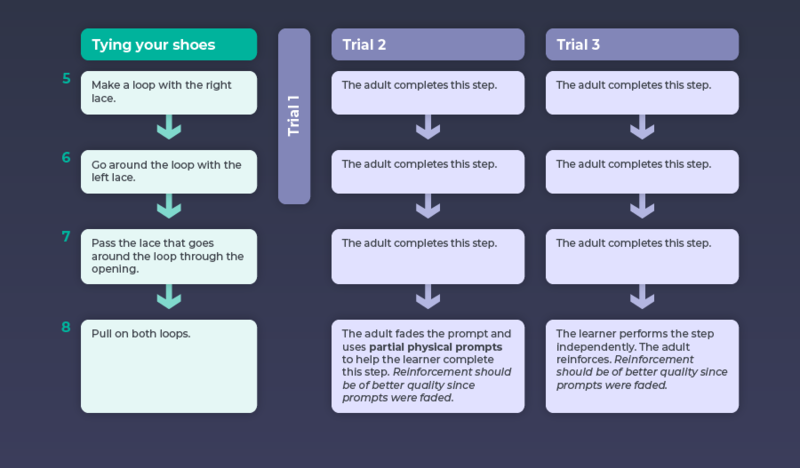

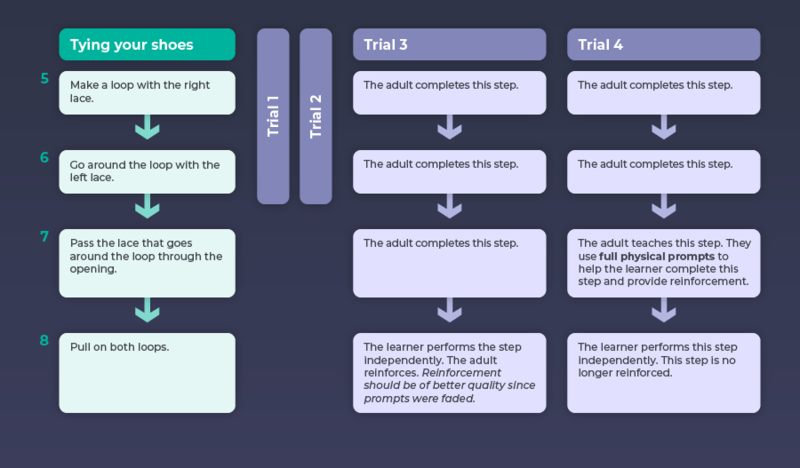

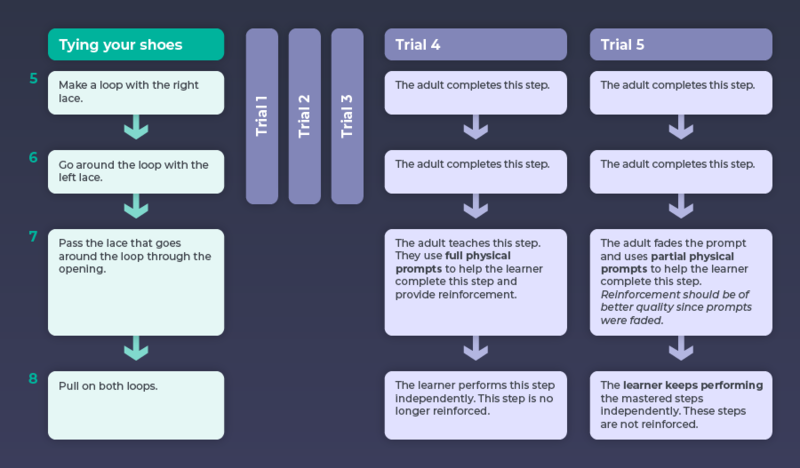

Here is an example of how the skill tying shoelaces can be taught using forward chaining:

Backward Chaining

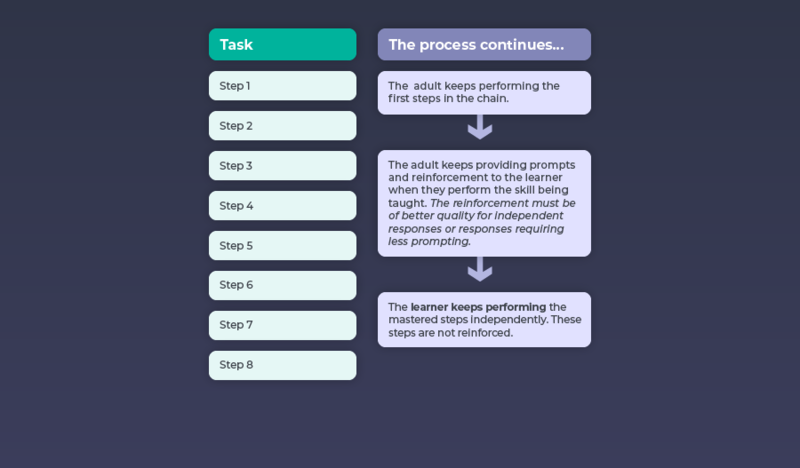

Backward chaining teaches the steps of the chain that have not been mastered, starting with the last step. The adult performs the first steps of the chain or helps the learner to do them and teaches the learner the last step using prompts and reinforcement. This constitutes a trial. During subsequent trials, the adult continues to perform the first steps in the chain and to teach the last step using prompts and reinforcement until it is mastered. The adult gradually fades the prompt from one trial to another, depending on the learner’s progress, and enhances the quality of the reinforcement provided for an independent response. Once the learner masters the step independently, the adult repeats the same teaching process for the previous step. Note that the steps the learner can do independently are no longer reinforced.

The individual thus learns to do one step at a time, but this step is never separated from the chain. The learner understands that one step leads to the next, which facilitates the transfer of learning.

Here is how the skill tying shoelaces can be taught using backward chaining:

Chaining Prerequisite Skills

Before using a chaining strategy with a learner, the adult must verify that the learner has the prerequisite skills to perform each step in the task analysis. These prerequisite skills vary according to the skill targeted. For example, before learners are taught to tie their shoelaces, they must be able to hold a shoelace between their fingers. To follow a recipe, they must be able to recognize the fractions (¼, ½, ¾) included in the recipe and associate them with the appropriate measuring tools.

Factors to Consider in Chaining

Examples of Skills Well-Suited to Task Analysis and Chaining

Task analysis and chaining apply to various domains and skills of the CALI – Functional Skills for Independence. The slideshow below provides examples of skills that lend themselves well to task analysis and chaining.

Task analysis and chaining are two evidence-based interventions that can be used to break down a complex task into small steps that are easier to manage for the learner. Task analysis is used to describe each of the steps, and chaining is the suggested strategy for teaching those steps. The most appropriate skills for task analysis are those that can be divided into small steps, including daily living, communication, social, and academic skills.

Learning Objectives

After working through this section, you will be able to:

- Develop and validate a task analysis;

- Plan task analysis and chaining by following the proposed steps;

- Implement the type of chaining chosen or guide the person responsible for implementing the intervention;

- Track learner progress and assess skills maintenance;

- Make appropriate decisions in a given scenario.

Developing a Task Analysis

The task analysis process consists of defining each of the steps or behaviours that occur as part of a larger sequence, or chain, to accomplish a task. Following are the steps for developing a task analysis:

1. Identify the steps in the chain.

There are three methods that can be used to identify the steps in the chain. Click each method to learn more.

Observe

Observe a skilled person going through the desired behaviour sequence.

Observe a skilled person going through the desired behaviour sequence.For example, you could watch another child tie their shoes and write down the steps you observe.

Consult

Consult specialists or people skilled in performing the task.

Consult specialists or people skilled in performing the task.A person who has taught a child to tie their shoes can help produce an effective task analysis.

Practice

Practice the behaviour; do the steps yourself.

Practice the behaviour; do the steps yourself. 2. Describe the steps in an observable, measurable, and accurate manner.

The more complete and accurate the task analysis is, the more successfully the learner will be able to acquire the skill.

It is more effective to describe the steps using action verbs and to include only one action per step. The steps must be adapted to the learner’s level (e.g., the steps will be more detailed for a younger learner than for an older learner).

3. Validate the steps.

Regardless of the method chosen, it is important to validate the steps and ensure that the material chosen corresponds well to the context and to the needs of learners and their families. All that is required is for another person (i.e., a colleague, another learner) to carry out the steps exactly as written in the list, using the materials indicated.

Click on the image to display a sample task analysis for the skill Washing hands.

This skill may be described differently depending on the context (e.g., washing hands at home or washing hands in a public washroom). That is why it is important to individualize the task analysis according to the learner’s needs and check with the learner or the learner’s parents that the list of steps is appropriate.

Chaining

Chaining is a method of teaching skills in several steps. This teaching approach is often used in combination with task analysis. It is based on the reinforcement of a specific sequence of behaviours leading to the acquisition of a targeted skill.

Chaining is a method of teaching skills in several steps. This teaching approach is often used in combination with task analysis. It is based on the reinforcement of a specific sequence of behaviours leading to the acquisition of a targeted skill.To use chaining, a step in the sequence is chosen as the teaching target. Two evidence-based approaches, prompting and reinforcement, are used to teach the targeted step. Thus, the learner is first prompted to perform the step, and the behaviour is encouraged by a reinforcer.

Since a task analysis comprises several steps, you need to decide which step will be taught first. There are two strategies, forward chaining and backward chaining, which determine which step in the sequence will be targeted for teaching.

Forward Chaining

Forward chaining teaches the steps of the chain in the order that they would normally occur (i.e., from the first to the last step) and offers reinforcement to the learner for each step taught. Then, the adult goes through the next steps or helps the learner to do them. This is a trial. During subsequent trials, the adult continues to teach the first step using the prompt and reinforcement until it is mastered, and completes the rest of the sequence themselves. The adult gradually fades the prompt from one trial to another as the learner progresses, providing higher-quality reinforcement for independent responses.

Once the learner masters the step independently, the adult repeats the same teaching process for the next step. At this point, the adult stops reinforcing the earlier steps that the learner can perform independently.

The individual thus learns to perform one step at a time, but this step is never separated from the chain. The person understands that one step leads to the next, which facilitates the transfer of learning.

For certain skills, such as tying shoelaces, pulling a zipper up or following a recipe, learners can simply observe the adult performing the steps they have not yet mastered. However, for certain skills such as washing hands, the adult will have to guide the learner physically.

Here is an example of how the skill tying shoelaces can be taught using forward chaining:

Here is the process. Note that only the first four steps of the task analysis are listed here as an example, and only four trials are represented. In this example, it takes two trials to teach the first step, and two trials to teach the second step. Teaching will need to continue until the learner is able to perform all the steps in sequence independently.

Backward Chaining

Backward chaining teaches the steps of the chain that have not been mastered, starting with the last step. The adult performs the first steps of the chain or helps the learner to do them and teaches the learner the last step using prompts and reinforcement. This constitutes a trial. During subsequent trials, the adult continues to perform the first steps in the chain and to teach the last step using prompts and reinforcement until it is mastered. The adult gradually fades the prompt from one trial to another, depending on the learner’s progress, and enhances the quality of the reinforcement provided for an independent response. Once the learner masters the step independently, the adult repeats the same teaching process for the previous step. Note that the steps the learner can do independently are no longer reinforced.

The individual thus learns to do one step at a time, but this step is never separated from the chain. The learner understands that one step leads to the next, which facilitates the transfer of learning.

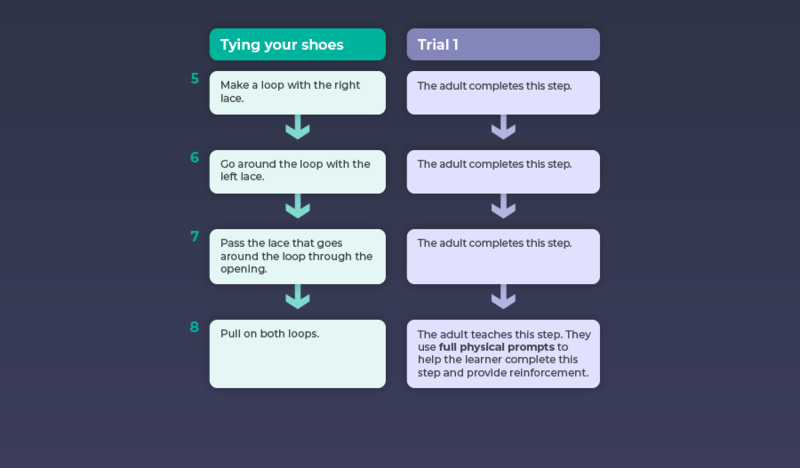

Here is how the skill tying shoelaces can be taught using backward chaining:

Here is the process. Note that only the last four steps of the task analysis are listed here as an example, and only five trials are represented. Teaching will need to continue until the learner is able to perform all the steps in the sequence independently.

Chaining Prerequisite Skills

Before using a chaining strategy with a learner, the adult must verify that the learner has the prerequisite skills to perform each step in the task analysis. These prerequisite skills vary according to the skill targeted. For example, before learners are taught to tie their shoelaces, they must be able to hold a shoelace between their fingers. To follow a recipe, they must be able to recognize the fractions (¼, ½, ¾) included in the recipe and associate them with the appropriate measuring tools.

Factors to Consider in Chaining

What type of chaining is the most appropriate?

The table below shows the advantages of each type of chaining and helps teams choose the most appropriate method for each learning situation.

During decision-making, the learner's current level must also be considered. If they have mastered a few steps at the beginning of the sequence, forward chaining is preferred. However, if they are more comfortable with the last steps of the task, backward chaining is more appropriate.

| Chaining | Advantages |

|---|---|

| Forward: Teach each step of the chain in the order it would normally occur |

|

| Backward: Teach each step of the chain beginning with the last one |

|

During decision-making, the learner's current level must also be considered. If they have mastered a few steps at the beginning of the sequence, forward chaining is preferred. However, if they are more comfortable with the last steps of the task, backward chaining is more appropriate.

How many trials will be necessary for learners to master a sequence of steps?

It is impossible to predict how many trials will be needed for learners to master each step independently. For some learners, one or two trials will be sufficient. For others, several trials will be needed before they master the step. It is important to increase opportunities to practice in order to speed up the pace of learning.

What type of prompt should be used to teach a sequence of steps?

The Prompting section provides information and example videos to help determine the type of prompt to use when teaching. The chosen type of prompt must match the type of skill taught. For example, a physical prompt is typically used to teach a motor skill and a verbal prompt is more effective to teach a language or a social skill.

It is possible to alternate the types of prompts from one step to the next or one trial to the next, according to the nature of the behaviour sought or how the prompt is working with the learner (e.g., using a full physical prompt for the first trial and changing to a modelling prompt for the second trial).

It is possible to alternate the types of prompts from one step to the next or one trial to the next, according to the nature of the behaviour sought or how the prompt is working with the learner (e.g., using a full physical prompt for the first trial and changing to a modelling prompt for the second trial).

When should the prompt be faded?

The adult must offer a prompt that is appropriate in quantity and intensity for the learner's needs. Offering too few prompts may lead to learner errors, whereas too many prompts may lead to prompt dependency. It is necessary to strike a balance. Here are some tips for recognizing the right time to begin fading the prompt:

- Speed of response: When learners begin to respond even before receiving a prompt, it may be time to begin fading.

- Initiative: When learners prefer to perform the movements alone and refuse physical prompts, it may be time to fade the prompt.

- Data: Consult data to determine the learner's real progress.

What should be done if learners are stuck at a certain step?

Trying a different type of prompt may help learners who have problems with one step in particular. If learners do not always succeed, they may be missing some prerequisite skills. Another member of the team such as a speech therapist, an occupational therapist, or a physiotherapist may help determine barriers to learning. For example, if learners have to open a container for a recipe, but are not able to do so independently despite the prompt, an occupational therapist might suggest accommodations or specific techniques to help them.

Examples of Skills Well-Suited to Task Analysis and Chaining

Task analysis and chaining apply to various domains and skills of the CALI – Functional Skills for Independence. The slideshow below provides examples of skills that lend themselves well to task analysis and chaining.

Examples of skills in the Fundamental Skills domain that can be taught through task analysis and chaining:

- Sorting during natural activities (e.g., sorting clothes)

- Telling a simple story in a logical order

Examples of skills in the Motor Skills domain that can be taught through task analysis and chaining:

- Assembling the parts of an object and taking them apart

- Tying shoelaces

- Drawing

- Painting

Examples of skills in the Daily Living Skills domain that can be taught through task analysis and chaining:

- Putting on and taking off various garments

- Washing hands

- Bathing

- Setting the table

- Making the bed

- Doing the wash

- Vacuuming

Examples of skills in the Social Interaction Skills domain that can be taught through task analysis and chaining:

- Answering the telephone

- Calling a friend

Examples of skills in the Functional Academic Skills domain that can be taught through task analysis and chaining:

- Filing letters in alphabetical order

- Following a recipe

- Sending an e-mail

- Completing an application or simple form

Examples of skills in the Community Skills domain that can be taught through task analysis and chaining:

- Performing a simple transaction using a debit card

- Withdrawing money from the automated teller machine

- Determining a suitable bus route using a map or bus schedule

Examples of skills in the Recreation and Leisure Skills domain that can be taught through task analysis and chaining:

- Sewing

- Woodworking

- Attending a concert

Examples of skills in the Self-Determination domain that can be taught using task analysis and chaining:

- Looking after your personalized support device

- Making a decision

- Setting an objective

-

Previous item Planning